I’ve just read a book that changes the way I think about the fires I light. I guess any book that gets us to think about things we overlook is worth sharing. And a book that moves us to change our daily ways of living might even get banned in some states. Imagine a book that might also be dangerous not to read.

I better confess that I don’t know how much I add to global warming. Do you know your carbon footprint? “Not much” has been my convenient assumption, mostly because I’ve had no clue about how to think about the question until I read John Vaillant’s Fire Weather (2023). Vaillant tells us first about the phenomenal 2016 fire storm, so big and fast that it decimated Fort McMurray, Alberta, in a day, burning on for 17 months. His gripping account of the fire sets up the last third of the book, titled “Reckoning,” the bigger story of our slow and reluctant reckoning with the elusive truth about the fires of “The Petrocene Age,” beginning in 1870.

In the late 1800s we figured out how to tap petroleum from the earth and turn it into controlled combustion fires that give us power. In fact, we’ve been so good at making fires out of fossil fuels that Vaillant writes: “Never in Earth’s history…have so many fires been ignited in so many places on such a continuous basis.”

Listen to an audio version of this blog on SoundCloud.

I never thought of myself as a pyro, but clearly, we all are. Every time I flick a light switch—maybe 50 times a day—or cook on our gas stove or mow the lawn or drive our car, I’m lighting uncountable combustions. When I think of all those engine cylinder fires that I’ve ignited under my accelerator pedal over my lifetime, it’s enough to make me wilt. Until I think of the fires burned by thousands of 18-wheelers and jets and cargo ships and factories…every day.

And that’s life, right? It seems so natural. How else should we live? “Behind the wheel of a Chevy Silverado, a one-hundred-pound woman can generate more than six hundred horsepower as she draws a six-ton trailer at sixty miles an hour while talking on the phone and drinking coffee, in gym clothes on a frigid winter day. Prior to the Petrocene Age, only a king or pharaoh could have summoned such power,” writes Vaillant. “Today…everyone’s an emperor.”

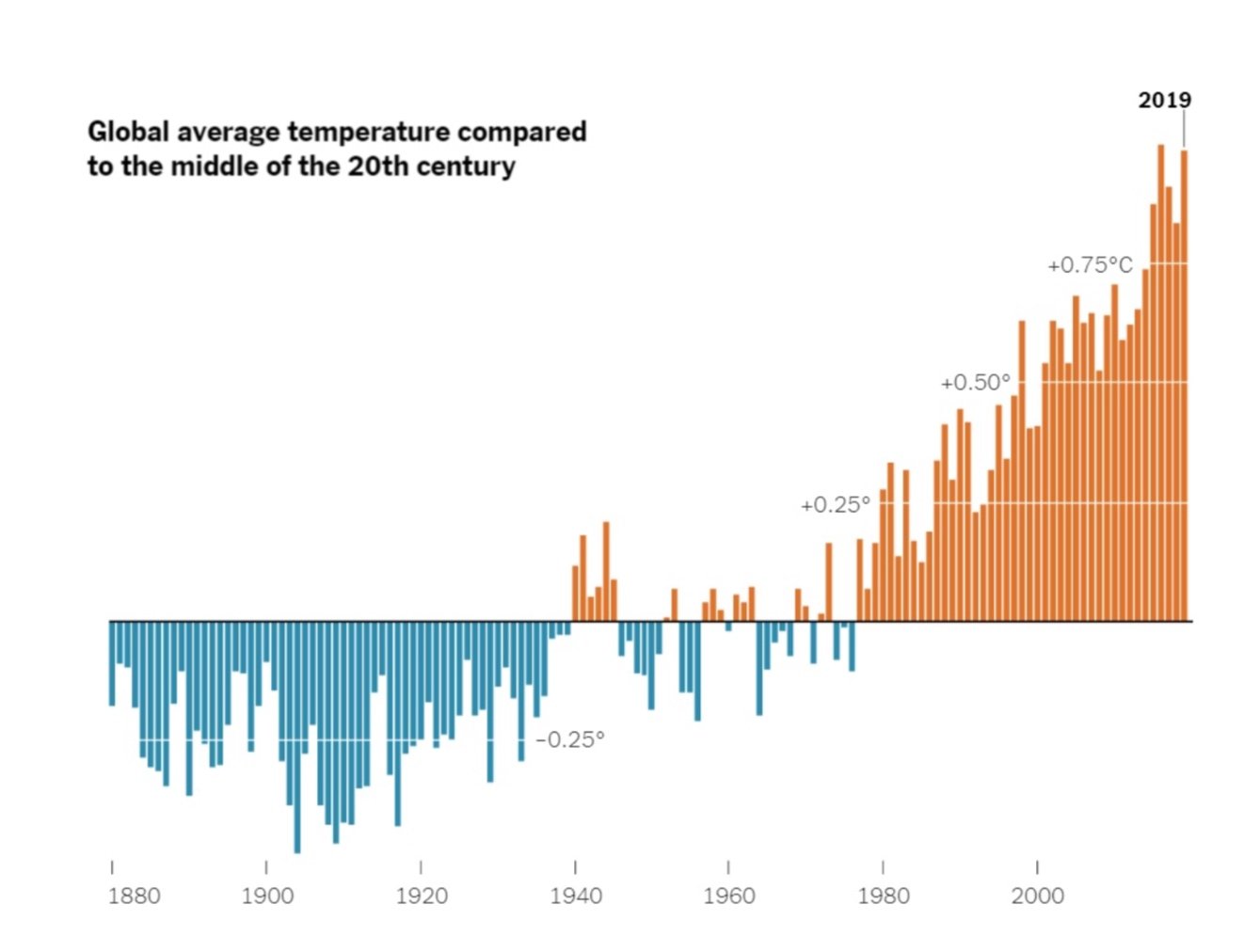

And we emperors are not likely to give up our power because of a few firestorms on the news somewhere else. We will ignore our contributions to global warming as long as nobody’s counting. It’s not easy to figure out your carbon footprint. I tried three different calculators (US EPA, Nature Conservancy, and Global Footprint Calculator) and got three very different answers based on very different information, most of which I don’t keep track of (such as the number of miles I fly each year). None of my friends have a clear idea what their carbon footprints are. An accurate count is clearly a complicated calculation for which we have no easy standard, so it’s easy to ignore. But if the IRS added a line to our 1040 forms taxing our carbon footprints according to some formula, wouldn’t we figure out quickly how to burn less carbon to pay less taxes?

Vaillant’s book raises the question for me of what it takes to become a climate activist. Can we divest from all petroleum-related industries? Can we cut down on buying petroleum products? Can we sue the oil companies for damages? Can we recycle in smarter ways? Can we make our carbon footprints public to shrink them more? Can we donate more to climate saving organizations? We can do all of this, with a fire nipping at our heels.

But it’s mid-October in Cincinnati where our leaves and our lawns are still green. We’ve had no fire weather in our corner of the globe, and our water flows freely from our rivers and aquafers to our faucets. Solar panels and windmills are still novelties here, not yet the way we power our empires. We love living by fire, and we can’t yet imagine dying by fire. We have a hard time believing this new kind of fire has become a force of Nature that already touches us all.

Vaillant leaves us wondering if our reckoning with climate science is coming too little and too late. It might be dangerous not to read this book and ask, What more do we need to change our ways? Whatever that change is, it better come big and fast.